By Tracey Muir, Julia Hill and Sharyn Livy

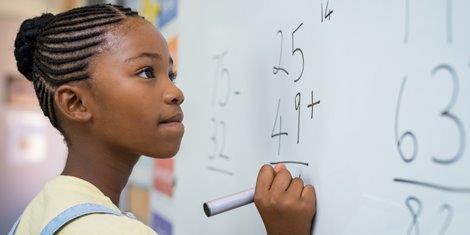

What do you remember about maths at school? Did you whizz through the problems and enjoy getting the answers right? Or did you often feel lost and worried you weren’t keeping up? Perhaps you felt maths wasn’t for you and you stopped doing it altogether.

Maths can generate strong emotions in students. When these emotions are negative, it leads to poor mathematical wellbeing. This means students do not feel good when doing maths and do not function well. They may experience feelings of hopelessness and despair, and view themselves as incapable of learning maths.

Poor mathematical wellbeing, if not addressed, can develop into maths anxiety). This can impact working memory (which we use for calculating and problem-solving) and produce physical symptoms such as increased heart and breathing rates. It can also lead to students avoiding maths subjects, courses and careers.

Research shows students often start primary school enjoying and feeling optimistic about maths. However, these emotions can decline rapidly as students progress through school and can continue into adulthood.

Our new, as-yet-unpublished, research shows how this can be an issue for those studying to become teachers.

Our research

We frequently see students enter our university courses lacking confidence in their maths knowledge and ability to teach the subject. Some students describe it as “maths trauma”.

To better understand this issue, we surveyed 300 students who are studying to be primary teachers. All were enrolled in their first maths education unit.

We asked them to recount a negative and positive experience with maths at school. Many described feelings of shame and hopelessness. These feelings were often attributed to unsupportive teachers and teaching practices when learning maths at school.

‘I felt so much anxiety’

The responses describing unpleasant experiences were highly emotional. The most common emotion experienced was shame (35%), followed by anxiety (27%), anger (18%), hopelessness (12%) and boredom (8%). Students also described feeling stupid, afraid, left behind, panicked, rushed and unsupported.

Being put on the spot in front of their peers and being afraid of providing wrong answers was a significant cause of anxiety:

The teacher had the whole class sitting in a circle and was asking students at random different times tables questions like ‘what is 4 x 8?’ I remember I felt so much anxiety sitting in that circle as I was not confident, especially with my six and eight times tables.

Students recalled how competition between students being publicly “right” or “wrong” featured in their maths lessons. Another student recalled how their teacher held back the whole class until a classmate could perfectly recite a certain times table.

Students also told us about feeling left behind and not being able to catch up.

In around Year 9, I remember doing algebra, and feeling like I didn’t ‘get’ it. I remember the feeling of falling behind. Not nice! The feeling of gentle panic, like you’re trying to hang on and the rope is pulled through your hands.

Students also described the stress of results being made public in front of their classmates. Another respondent told us how the teacher called out NAPLAN maths results from lowest to highest in front of the whole class.

‘I was scared of maths teachers’

In other studies, primary and high school students have said a supportive teacher is one of the most important influences on their mathematical wellbeing.

In our research, many of the students’ descriptions directly mentioned “the teacher”. This further shows how important the teacher/student relationship is and its impact on students’ feelings about maths. As one student told us, they were:

[…] belittled by the teacher and the class [was] asked to tell me the answer to the question that I didn’t know. I felt lost and embarrassed and upset.

Another student told us how they were asked to stay behind after class after others had left because they didn’t understand “wordy maths problems”.

[there were] sighs and huffs from the teacher as it was taking so long to learn. I was scared of maths and maths teachers.

But teachers were also mentioned extensively when students reflected on pleasant experiences. Approximately one third of student responses mentioned teachers who were understanding, kind and supportive:

In Year 8 my teacher for maths made it fun and engaging and made sure to help every student […] The teacher made me feel smart and that if I put my mind to it I could do it.

What can we do differently?

Our research suggests there are four things teachers can do differently when teaching maths to support students’ learning and feelings about maths.

1. Work with negative emotions: we can support students to tune into negative emotions and use them to their advantage. For example, we can show students how to embrace being confused – this is an opportunity to learn and with the right level of support, overcome the issue. In turn, this teaches students resilience

2. Normalise negative emotions: we can invite students to share their emotions with others in the class. Chances are, they will not be the only one feeling worried. This can help students feel supported and show them they are not alone

3. Treat mathematical wellbeing as seriously as maths learning: teachers can be patient and supportive and make sure maths lessons are engaging and relevant to students’ lives. When teachers focus on enjoying learning and supporting students’ psychological safety, this encourages risk-taking and makes it harder to develop negative emotions

4. Ditch the ‘scary’ methods: avoid teaching approaches that students find unpleasant – such as pitting students against each other or calling on students for an answer in front of their peers. In doing so, teachers can avoid creating more “maths scars” in the next generation of students.

Muir is Professor in Education (STEM), Australian Catholic University, Hill is Lecturer in Mathematics and Numeracy Education, The University of Melbourne, Livy is Senior Lecturer, Mathematics Education, Monash University

The Conversation