“Weak governance” is a popular scapegoat for the poor results achieved by South Africa’s education system. And there is no doubt that many aspects of how the education bureaucracy operates are problematic.

But what about setting the scapegoats aside for a moment and seeking solutions? One way to do this is to look elsewhere for inspiration. So, in that spirit, consider Kenya. For much of the half-century since it became independent the East African nation had been an over-performer on the continent in its measured education outcomes.

To get a sense of Kenya’s historical overperformance, consider the 2007 results of standardised tests for sixth graders conducted by the Southern and East African Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality. Kenya’s average score was 557 points. That’s well above South Africa’s average of 495 points. Kenyan children’s basic literacy and numeracy skills were stronger than South Africa’s.

Kenya has a much lower per capita income than South Africa. In part as a result, its public spending on education per pupil is only one-fifth that of South Africa. Its educational bureaucracy is relatively messy.

Despite all this, as the graph in a more extended discussion underscores, it has historically been an over-performer in southern and eastern Africa, both relative to South Africa and more broadly.

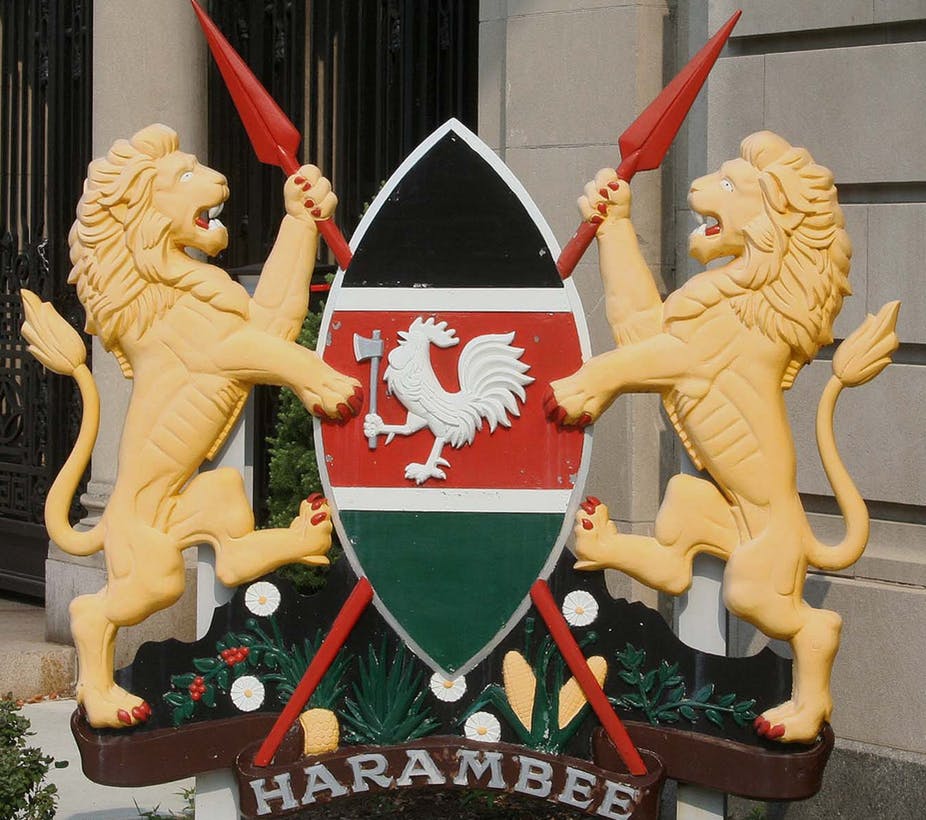

How did this happen? The answer lies with active civic engagement. Kenya’s first president of the independence era, Jomo Kenyatta, championed this in the form of a self-help ethos known as “Harambee” as the pathway to development, including a strong focus on educating the country’s citizenry. For years after his tenure as head of state ended, the principle remained deeply embedded in Kenyan society – and the country’s education system.

There could be valuable lessons here for South Africa. Kenyans believe that fixing education is not someone else’s task or someone else’s failure. It involves active citizenship and proactive engagement at all levels: public officials; principals, teachers and their unions; parents and communities.

Perhaps what South Africa needs now is not a top-down government policy of “education for all” – but rather, “all for education”.

Kenya’s history of Harambee

In an email exchange with me, Dr Ben Piper, a seasoned educational specialist and long-term resident in Nairobi, identified some key things that he finds remarkable in Kenya:

…[I]n rural Kenya there is an expectation for kids to learn and be able to have basic skills … Exam results are far more readily available than in other countries in the region. The ‘mean scores’ for the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) and its equivalent at secondary school are posted in every school and over time so that trends can be seen. Head teachers are held accountable; paraded around the community if they did well, or literally banned from school and kicked out if they did badly.

This sort of accountability and community involvement forms part of the “softer” dimensions of school governance. And the roots of this approach run deep. They were part of the foundational ideas that shaped modern Kenya.

Jomo Kenyatta was a powerful advocate for better quality education. His focus on education persisted during his activist days, through his years in the UK and in his role as director and principal of the Kenya African Teachers’ College, run by the independent schools movement.

He became independent Kenya’s first president in 1963 and immediately offered a vision of a nation imbued with Harambee (“let us pull together”). The country adopted the term as its official national motto. As numerous studies have underscored, engagement with education held pride of place within the Harambee movement.

Harnessing existing structures

The key to turning around South Africa’s education system may be to spend less time deciding who to blame and more seeking out renewed opportunities for engagement.

This wouldn’t involve reinventing the wheel. The country’s institutional framework for education, promulgated in 1996, creates multiple entry points for participation by a variety of stakeholders.

School governing bodies, which consist mostly of parents, can play a central role. These bodies are generally in the news for all the wrong reasons; as tools for elites to keep control of their schools, and as sites of corruption. Indeed, the South African government’s recent Basic Education Laws Amendment proposal, following an investigation of ‘jobs for cash’ scandals in schools, proposed scaling back the authority of school governing bodies.

But, as I’ve written elsewhere, research at school level also shows that school governing bodies can be a source of resilience, including in poor communities.

Perhaps the crucial lesson from Kenya’s history is that our current discourse has it backwards. Fixing education is not someone else’s task, and someone else’s failure. Active citizenship implies pro-active engagement at all levels – by public officials, by principals and teachers (and their unions), by parents and communities.

If South Africa is willing to learn from Kenya, what is called for now is not another top-down “education for all” target from government –- but rather “all for education”.

This article was first published on The Conversation Africa