The “what if” game is popular with the media and the commentariat in South Africa. A popular example is “what if …” South African Communist Party (SACP) leader Chris Hani were still alive.

What, for example, would he say about the SACP’s tripartate alliance partner, the ANC? What would he say about the state of the alliance after recent calls by both partners, the SACP and union federation Cosatu for President Jacob Zuma to step down?

These questions are being asked again on the anniversary of Hani’s assassination on April 10, 1992 by two rightwing extremists.

But such use, often by the liberal media, of Hani’s name (and those of other fallen cadres of the liberation movement) is problematic. It seeks to isolate Hani from the movement that produced him, presenting him as an exception it can then appropriate.

Hani’s name is also regularly invoked by the SACP and the ANC come election time. Many campaign posters call on supporters to “Do it for Chris Hani”. Here, the summoning of Hani’s memory has become little more than empty rhetoric.

A more useful exercise may be to reflect on Hani’s life, actions and beliefs, and their significance for today.

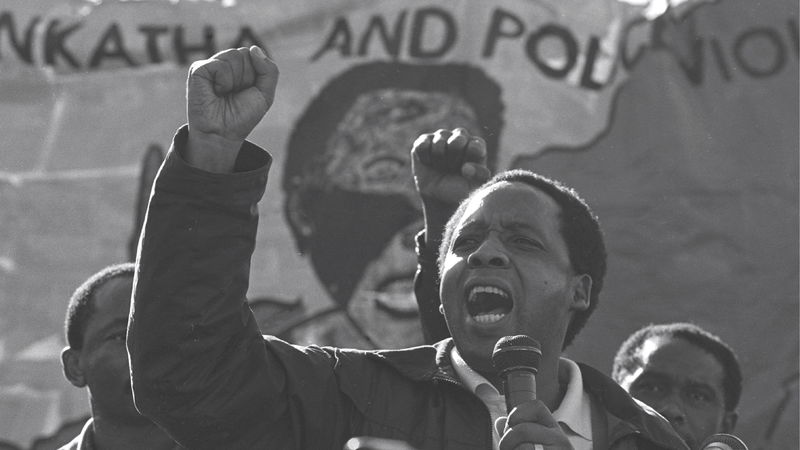

A popular hero

In his book “A Jacana Pocket Biography: Chris Hani” historian Hugh Macmillan argues it was Hani’s physical and moral bravery, his compassion and humanity that made him a “popular hero” – the words used by French philosopher Jacques Derrida to describe Hani in his Spectres of Marx lecture.

Hani helped build a culture of internal criticism in the ANC. In 1969 he and six other commissars and commanders of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s military wing, signed what became known as the “Hani memorandum”. The memorandum outlined the “frightening depth of the rot in the ANC”, accusing its leadership of careerism, corruption and persecution by the party’s security.

Hani’s memorandum was the catalyst for one of the most significant events in the history of the ANC in exile, a conference in Morogoro, Tanzania. But it was viewed as treacherous by some within the leadership, particularly those it had criticised. Hani and his comrades were expelled from the ANC and only reinstated after the Morogoro conference.

The Morogoro conference opened ANC membership to non-Africans. It also adopted the important “Strategy and Tactics” document. This provided – for the first time since the ANC’s banning in 1960 – a systematic assessment of the conditions of struggle and an overall vision for defeating apartheid in a time of deep political demoralisation.

The conference was a moment of self-reflection. It helped the ANC to overcome the state of crisis and demoralisation that had set in.

The ability of the leadership of both the ANC and its closest ally, the SACP, to reassess circumstances, interrogate these and themselves, and learn from past mistakes to overcome difficult moments is one of the most important lessons from their history. This tradition of internal debate has become eroded, and criticism keeps being silenced as sowing disunity.

Disrupting notions of masculinity

A famous quote by Che Guevara states that “the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love”. Leaders like Hani were moved to act by their hearts as well as by reason. The decision to join the liberation struggle was one of reason – a conscious rejection of apartheid oppression and inequality. But it was also a choice informed by “revolutionary love” or a “love for the people” – shaped by a sense of justice and by compassion, as well as by a vision, the ability to imagine a different future.

As struggle veteran and public intellectual Raymond Suttner points out in Recovering Democracy in South Africa, what is new and alarming about many of the ANC’s current leaders is their callousness. The plight of the poor no longer evokes compassion or empathy from a government that is supposed to represent them.

Both Suttner and Macmillan also highlight Hani’s commitment to disrupting notions of heroic masculinity. In his book Macmillan tells the story of one of Hani’s comrades Thenjiwe Mtintso who credited him with introducing her to the gender content of the liberation struggle when she arrived in exile.

Hani’s concern with gender issues can also be seen in his reaction to the abuse of women in MK camps. He introduced a rule that prevented officers from forming relationships with new women recruits.

By looking at the life of people like Hani South Africans can recover the possibility of alternative and gentler types of masculinity to the prevailing models of patriarchal, machoist, militaristic and violent manhood.

Communist for life

At the time of South Africa’s transition to democracy Hani decided to resign from ANC structures and concentrate his efforts on building the SACP. He understood that there would be a need to build the party for it to be a truly democratic and democratising force in a post-apartheid South Africa intent on taking the struggle of the working class and the poor forward.

While the SACP would have to redefine itself in the new South Africa, Hani believed that it should be the main agent of change. That’s where his loyalty to the party was rooted.

Hani was not a communist in passing. He immersed himself completely into the liberation struggle. And it was “a communist as communist”, to quote Derrida again, that his assassins were out to get.

The story of his life –- and that of many others –- is exemplary of this total commitment and willingness to sacrifice one’s life for an ideal. It was ideas, a political project and the movement that counted – not individuals, because no one would have made it on their own.

This may be difficult to imagine in today’s society where individualism and self-interest reign supreme and personalised politics has become the norm. But it was by doing things with, and for others, as part of a collective movement that people like Hani found their self-realisation.

Arianna Lissoni, Researcher at History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand.

Read the original article here